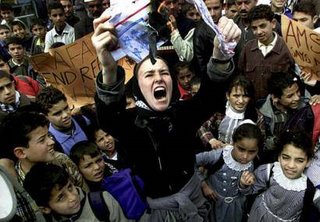

My name is Rachel Corrie St. Pancake

This morning's New York Times theater column includes an unenthusiastic review of "My Name is Toward the end of the performance I attended, I heard one man choking back sobs and another snoring. I could sympathize with both responses.

...

The play, directed by Mr. Rickman, is not an animated recruiting poster for Palestinian activists. Its deeper fascination lies in its invigoratingly detailed portrait of a passionate political idealist in search of a constructive outlet. And its inevitable sentimental power is in its presentation of a blazing young life that you realize is on the verge of being snuffed out. (I kept thinking of the letters from Julian Bell, Virginia Woolf’s nephew, who was killed in the Spanish Civil War.)

The play’s most obvious hold on the audience’s attention comes from its being structured as a sort of countdown to a tragic death. The very look of the stage at the beginning — in which Rachel’s bedroom in Olympia, Wash., seems to float against a ravaged Middle Eastern townscape — presages a journey we know will be fatal.

It is all the more surprising, then, to discover that for long stretches “Rachel Corrie” feels dramatically flat, even listless. This is not the fault of the text. From earliest adolescence, Ms. Corrie, who wanted to be a poet, had a voice that was unusually and emphatically her own, and a precocious gift for concrete metaphors that give form to nebulous feelings.

To read what she wrote in the last decade of her short life, as assembled by Mr. Rickman and Ms. Viner, is to perceive sometimes eerie patterns of recurring images, with that sense afforded only by hindsight of how each human existence seems to possess its own poetic structure.

...

Her Rachel is most compelling after she has arrived in Israel, and later Gaza, when her childhood habit of making lists — of things to do, of items needed — to keep chaos at bay acquires a heartbreaking urgency. No matter what side you come down on politically, Ms. Corrie’s sense of a world gone so awry that it forces her to question her “fundamental belief in the goodness of human nature” is sure to strike sadly familiar chords.

Unfortunately, what should have caused to her to question her “fundamental belief in the goodness of human nature” - seeing people allowing their homes to be used for weapons tunnels - did not.

Unfortunately, what should have caused to her to question her “fundamental belief in the goodness of human nature” - seeing people allowing their homes to be used for weapons tunnels - did not.I also trust that the play does not show or discuss this scene. It might even be too much for some denizens of Greenwich Village to handle.

2 Comments:

http://www.keshertalk.com/archives/2006/10/rachelcorrieplay3.php

"St Pancake" indeed. What wit. Clearly you have no conception of sympathy with those grioeving the loss of a daughter, friend, and generally worthwhile human being. Clearly you are not one such.

You are a fake Jew, right? Because most of the Jews I know are sensitive to suffering: some even survived the Holocaust. Do you believe in that, or do you call camp survivors "St Zyklon"?

Post a Comment

<< Home